The UK Gambling Commission has recently set out an ambition for its voice to be “authoritative, trusted and impartial”. Yet its good intentions are undermined by an impending muddle on problem gambling prevalence rates…

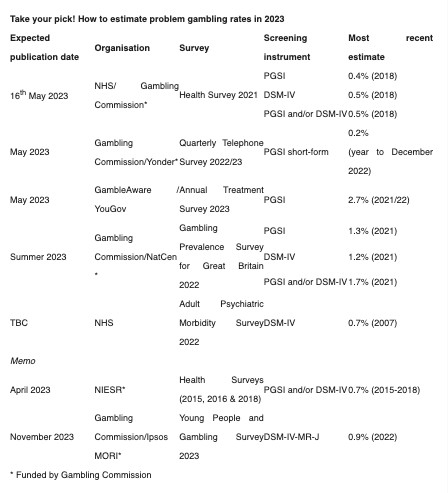

In a little over a week, the NHS will publish Part Two of its Health Survey for England 2021 – a dataset that includes estimates of gambling participation and problem gambling prevalence. Based on results from previous surveys in 2012, 2015, 2016 and 2018, we may expect the PGSI ‘problem gambling’ rate to be somewhere between 0.4% and 0.6% of the population (16 years and over). The fact that it covers a period of significant disruption to betting behaviours might suggest a lower figure – although Covid-enforced changes to data collection could muddy the waters.

A month or so later, the Gambling Commission will publish its own Gambling Prevalence Survey for Great Britain. Based on results from a small-sample pilot survey conducted in January 2022, its central estimate of PGSI ‘problem gambling’ may lie between 1% and 2% – although it could be higher. In between these two events, the Gambling Commission will publish its latest estimate of ‘problem gambling’ using the PGSI short-form questionnaire from its Quarterly Telephone Survey (a rate that stood at 0.2% for the 12 months to December 2022).

The NHS is also preparing to publish the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2022. The last time that this survey (which is conducted every seven years, pandemics permitting) contained gambling information was in 2007, when it reported a DSM-IV ‘problem gambling’ rate of 0.7%.

We anticipate that the state (Gambling Commission and NHS) will publish at least eight different rates of ‘problem gambling’ (16 years+) this year – although this rises to 11 if we factor in the quarterly iterations of the Commission’s telephone survey. Supplementing central estimates with lower and upper bound figures adds another 14, to take the total to 25 different rates of ‘problem gambling’ reported by state agencies. In addition, there is the much-abused Young People and Gambling Survey, which assesses rates of DSM-IV-MR-J ‘problem gambling’ among schoolchildren aged 11-16 years (and is not even remotely comparable with the adult surveys).

A recent report from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (funded by the Gambling Commission) has estimated that 0.7% of the population are likely to be ‘problem gamblers’ under DSM-IV and/or PGSI criteria (a figure based on the weighted averages from the Health Surveys in 2015, 2016 and 2018). Finally, there is the GambleAware Annual Treatment Survey (also imminent) that is likely to put the figure somewhere between 2.5% and 3.0%. Hardly anyone outside of GambleAware considers this survey (which uses a YouGov non-random, self-selection online panel) to be reliable – and there is an irony that the most histrionic claims originate (once again) from an industry-funded study.

Of the seven different surveys, five have been funded by the allegedly cash-strapped Commission. Only two however, will be able to lay claim to Official Statistics status. The Health Survey for England 2021 will briefly hold sway before being supplanted by the Commission’s new survey. It seems plausible therefore that the Official Statistic may change significantly in a matter of weeks. The Commission has already said that it “makes no apology” for this. This is no surprise.

The Gambling Commission has never knowingly apologised for anything in the last five years (a consequence perhaps of simply not knowing where to start). It ought however to take with greater seriousness the potential consequences of its actions in this domain.

In January this year, the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (‘OHID’) published its estimate that either 117 or 496 deaths by suicide each year in England are associated with problem gambling. These claims, which are thoroughly bone-headed (if not dishonest – see Inflating the harms of gambling – Cieo) are based, in part, on results from the Health Survey for England 2018. Had the OHID based its calculations on the Gambling Commission’s pilot survey, its suicide estimate would have been somewhere in the region of 1,750 – or around 30% of all such deaths (using GambleAware’s figures, the number rises to more than 3,500). That claims about such a serious matter may be changed so dramatically and upon a whim ought to demonstrate the speculative nature of the entire OHID enterprise – but the gambling ‘debate’ departed for post-truth some time ago; and there is never any shortage of willing adherents to catastrophism.

Documents released last year under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that the Gambling Commission itself has speculated about ways in which prevalence surveys might be used to increase suicide estimates (a truly morbid interest).The publication of the new survey may have significant practical consequences for consumers and operators alike.

Towards the end of 2022, the Commission consulted on changes to the Licence Conditions and Codes of Practice to require remote operators to conduct ‘safer gambling interactions’ on a minimum annual quota basis. If the regulator proceeds with its plans then online sportsbook operators will be required to conduct potentially quite intrusive interactions with around 4% of their customers each year, rising to around 9% for online casinos. These quotas may therefore increase, dramatically and arbitrarily as a result of the Commission’s decision to move away from the ‘gold standard’ NHS Health Survey; causing significant inconvenience to recreational consumers and substantially higher business costs.

Such requirements might be considered reasonable – although quota systems are not without their problems – if the survey results can be trusted. As Forrest & McHale’s Patterns of Play analysis showed, only a very small proportion of online gamblers received ‘safer gambling interactions’ between 2018 and 2019 (we must hope that matters have improved since then).

Sadly, the Gambling Commission’s pilot survey cannot be trusted. Comparisons with audited data show that it substantially over-reported participation in betting exchange as well as non-remote casino, bingo and the football pools (the four verticals we were able to test). The researchers involved in the pilot also failed to consider the plausibility of their findings (and in particular their test for reliability of problem gambling estimates) given the impact of lockdown measures that shuttered betting shops for 28% of 2021 and casinos, bingo clubs and arcades for 37%. The Gambling Commission does not dispute this criticism – but neither has it taken steps to address it.

The market regulator has thus placed itself in the position of indicating that the population prevalence of ‘problem gambling’ is – at the same time – both a highly important statistic and one where accuracy and robustness are irrelevant. Under these conditions, the prevalence rate assumes a political rather than a practical aspect – a football to be booted back and forth between legions of campaigners, lobbyists, parliamentarians and bureaucrats in support of predetermined agendas.

There is a perverse logic at play here. For public health activists (i.e. those who claim to want to improve health outcomes), the population prevalence rate of ‘problem gambling’ can never be high enough. The Advisory Board for Safer Gambling, for example, dropped as a Key Performance Indicator, a 50% reduction in the rate of ‘problem gambling’ when it realised that it might actually be achieved. The Gambling Commission has placed itself within this miserabilist throng by its insistence – as an article of faith rather than a matter of scientific enquiry – that all surveys (including its new one) systemically produce under-estimates. On the other hand, some industry participants continue to trot out the tired platitude that “one problem gambler is one too many” (a creed that invites some interesting questions, if viewed in earnest), or simply pick the lowest available figure and run with it without wondering whether it is the most robust or how the data might change.

Caught between catastrophism and cliché, it is difficult to see how any of this advances consumer or societal interests. As the late Peter Collins observed, “the futility and balefulness of trying to estimate national problem gambling numbers becomes even clearer when we consider that, even if we knew, even approximately, how many problem gamblers there are in the country, nothing would follow about what we should be doing the better to secure the objectives of the Gambling Act.”

Featured article edited by SBC from ‘Winning Post’ Monday 8 May 2023 (click on the below logo to access the full unedited analysis of Winning Post).