2020 has been the year of esports. As fewer and fewer sports events could take place due to COVID-19 in 2020, esports matches continued to be played online.

The betting industry has caught up. Where esports used to be a side note before, there are now entire betting portals dedicated just to esports. And no traditional bookmaker will now be caught without offering esports odds. As a data and odds provider, Bayes Esports was one of the drivers behind this process.

The current momentum for esports is quite obvious, both in terms of the number of fans and from a betting perspective. But this isn’t the momentum we’re talking about. Instead, we wanted to look into so-called psychological momentum that occurs during an esports match.

Psychological momentum is formally defined as a change in psychological or physiological behaviour caused by precipitating events that cause a shift in performance. The betting industry believes very strongly in the existence of momentum.

We might hear commentators say that a team is “on a roll”. Match momentum is defined similarly – what happens in the first map influences what happens in the second and, therefore, in the match.

Whether or not momentum actually exists has been debated for the last 40 years, with researchers finding both evidence for and against momentum in various sports. No such study has been conducted for esports yet.

Yet with access to a large body of professional esports data as well as odds, Bayes Esports is in a position to do so. In this article we give a preview of our findings.

In particular, we have looked at Counter-Strike Global Offensive (CS:GO) and Dota 2. Both are major esports titles that are played in teams of five. A match usually consists of several maps, where winning each map gives you a point. We look at the most common format: best of three.

The question we ask is whether or not winning the first map in a match gives you an advantage for winning the second map and, therefore, the match.

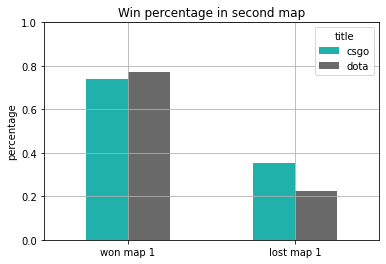

While we can simply check how often a team wins the second map after losing or winning the first map, as we can do with the bar chart above, this is not enough. Teams are not equally strong. If a team is a strong favourite, they are also a strong favourite to win both maps and momentum has nothing to do with it.

In order to have fair statistical analysis, we have to control for team skill. This is where a lot of problems usually arise – it is impossible to know the true skill of each team, only an estimation can be made.

In our data, we use Sportradar betting odds to estimate the skill (and therefore the win probability) of the CS:GO teams and Datdota Elo ratings for the Dota 2 teams. Both skill measures are equally good at predicting the winner.

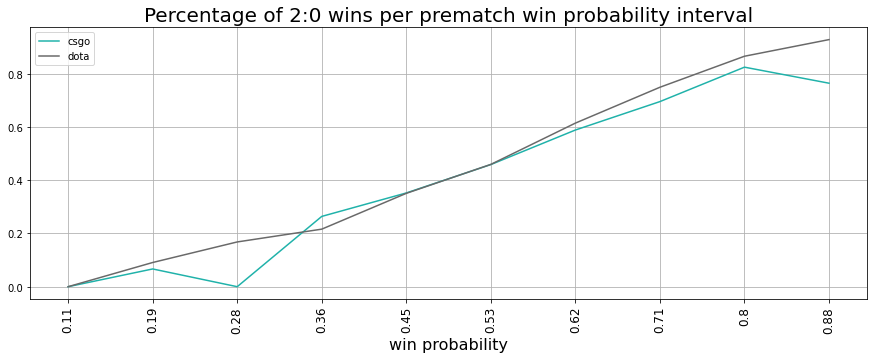

In both sets, the team skills are normally distributed. As we would expect, the percentage of 2:0 wins increases as the team skill increases for both titles, though not equally.

In traditional sports, momentum studies need to control for a number of other factors. In team sports, there is the home team advantage. In tennis, there is the type of court and the serve. In chess, there is a white advantage.

Esports typically do not have home and away teams, but they do have their own challenges when trying to fit statistical models to the data. In fact, the difference between the two lines in the above plot is due to the inherent differences in Dota 2 and Counter-Strike.

CS:GO is a first person shooter. Each map consists of rounds in which one team plays terrorists and the other counter-terrorists. After 15 rounds, the teams switch sides. Whoever gets to 16 points first, wins. If the score reaches 15:15, the game goes into overtime. Statistically that’s only about 10% of the matches.

There are currently seven different maps that CS:GO can be played on. At the start of each match, there is a map vote period that ends with each team selecting one map and a third map being drawn somewhat randomly as a decider. All maps have different advantages and disadvantages and not all teams play all maps equally well.

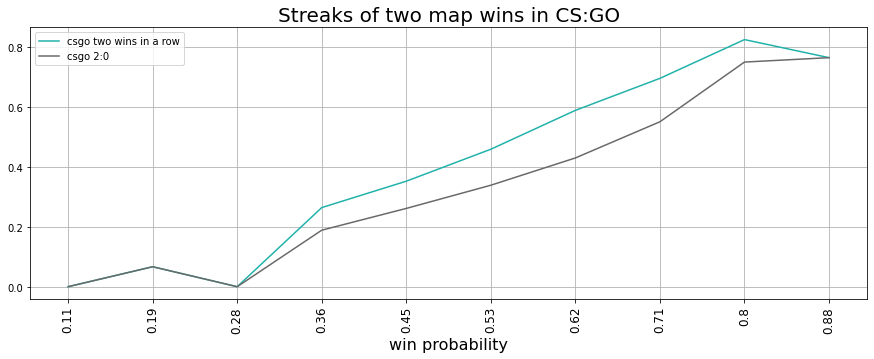

So a team might lose the opponent’s map, making the score 0:1, but then go on to win their own map and the decider, finishing 2:1. In fact, in 55% of all CS:GO matches the team who lost the first map but won the second goes on to win the last map.

In Dota 2, a MOBA title, there is only one map and a map selection effect doesn’t exist. The variation between games is achieved by teams selecting different heroes they want to play from a large pool.

What matters is which side can start choosing heroes first. The teams also choose sides – called Radiant and Dire. There is a small statistical advantage in playing Radiant that translates to a 1-2% higher win percentage.

Our Dota 2 data does not have information on who picked the first hero, but it does tell us which side the map was played on. It turns out that which side map 2 is played on is indeed significant for predicting who is going to win. Controlling for map side and pre-match win probability, we find that winning map 1 is significant when predicting who is going to win the second map at p=0.05 level.

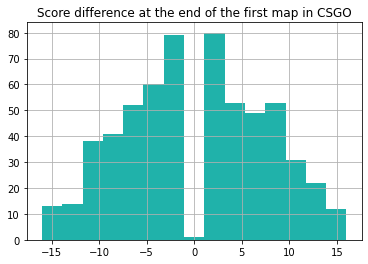

For Counter-Strike, we first thought that the difference in rounds after the end of the first map might turn out to be more significant than whether or not the map was won. This seems very likely, after all, the larger the difference in rounds is, the more convincingly you have won.

We do not find such an effect, however, when controlling for team strength. There are several interpretations we can give for this finding – perhaps teams accept defeat on one map and want to move on quickly to the next, or too much of the round win difference is already encoded in pre-match win probability (the correlation sits at 0.38). Finally, the score difference is influenced by which side the stronger team plays first – if they start on the “harder” side, the score difference will be smaller.

What does appear to matter is whether the map went into overtime or not. This makes sense intuitively, since it is an extreme measure of how closely the two teams are matched on a given map. When controlling for overtime, along with team strength, we find that winning map 1 is significant for predicting who will win map 2 in CS:GO as well as in Dota 2 at p=0.05 level.

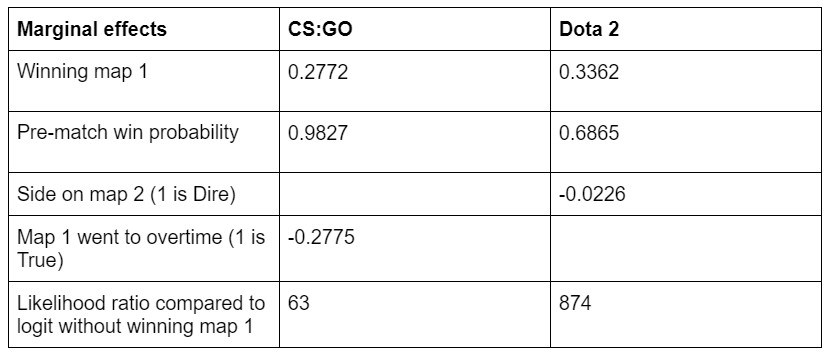

The table below shows the marginal effects assigned to the different regressors we used in the model. These can be read as “if the variable increases by one unit, the probability of winning the second map increases proportionally by the value of the marginal effect of that variable.”

We see that winning the first map gives you a 28% increase in probability for CS:GO and a 34% increase in Dota 2. This is consistent with the idea that map selection matters a lot in Counter-Strike.

Based on the assumption that our skill estimations are correct, our research shows that momentum in esports does exist between maps and betting odds should be adjusted after the first map is decided.

What exactly causes momentum and how it can be quantified and triggered remains an exciting topic in the sports analytics community that we consider ourselves part of.

In future research, Bayes Esports is going to look deeper into map selection in Counter-Strike as well as momentum on a single map.

This article was written by Darina Goldin, Director Data Science at Bayes Esports.