The UK’s Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) has updated research and analysis on gambling-related harms required by DCMS, ahead of the planned release of the 2005 Gambling Act review White Paper, detailing some key differences of opinion between stakeholders.

The evidence presented is a follow-up to the original Public Health England (PHE) report published in September 2021, which included the first analysis on the economic costs of gambling harms on UK society.

PHE was disbanded in March 2021, with its research functions transferred to OHID, which was tasked with providing the 2023 update. OHID cited that it had undertaken a full review of the review’s methodology analysing suicide and depression estimates, as areas that “held the largest contribution to overall costs.”

The review’s objectives are “to estimate the financial costs to government and the societal value of the health impacts associated with gambling-related harm experienced by the English population classified as gambling at levels of elevated risk and problem gambling”.

Of significance, the report argues that 0.5% of the British population ‘reached the threshold to be considered experiencing problem gambling’, based on Health Service for England (HSE) data from 2018.

This is higher than the UK Gambling Commission’s (UKGC) official figures from last year, which put the problem gambling rate in the UK at 0.2%, something which has been repeatedly pointed to by stakeholders such as the Betting and Gaming Council (BGC) as indicative of the industry’s existing player protection methods’ strengths.

Overall, PHE estimates that the total costs of harm across the UK covering a variety of areas and markers stands at £1.05bn-1.77bn, attributed to both government costs and wider negative societal outcomes.

Total health harms ranged from £754.4m-£1,475bn, attributed to deaths from suicide (£241.1m-£961.7m), depression (£508m), homelessness (£49m) and alcohol dependence (£3.5m) among adults, as well as illicit drug use among 17-24 year olds (£1.8m).

Regarding suicides, PHE’s judgement on the wider societal costs stems from an estimate of between 117 and 496 deaths per year.

Gambling reform organisation Gambling With Lives (GWL) asserts that there are over 400 deaths annually, so it is unclear whether the PHE supports or contradicts this claim.

The report’s analysis of stakeholders’ views on problem gambling and associated harm found some sharp differences between those who work in the industry and those calling for reform.

An analysis using 302 respondents alongside 929 tweets from 669 individuals identified eight categories of harm – general and health harms; financial, relationship, work or study, criminal and cultural harms; and ‘miscellaneous’ harms that could not be otherwise categorised.

Overall, the groups most likely to participate in gambling were those with ‘higher academic qualifications’, those who are in employment and not in generally deprived groups.

However, deprived groups were deemed to be at the greatest risk of gambling related harm, and the demographic was further narrowed down to young males as the most at-risk group.

PHE explained: “The socio-demographic profile of gamblers appears to change as gambling risk increases, with harmful gambling associated with people who are unemployed and among people living in more deprived areas. This suggests harmful gambling is related to health inequalities.”

As such there is also a major disparity in mental health between the two groups, with regularly participating gamblers having ‘better general psychological health and higher life satisfaction’.

In contrast, among the deprived high-risk population there are more noticeable levels of poor health, low life satisfaction and wellbeing, whilst the report also noted that people with poor psychological health are ‘less likely to report gambling participation’.

However, the review concedes that “given data limitations”, it is not possible to cost individual financial harms to gamblers or affected others (family, friends or individual networks impacted by others gambling).

Problem gambling analysis continues to rely on qualitative best available evidence, such as specific literature and analysis taken from separate reports.

As such the report recognises that “most of the evidence has not attempted to or not been able to establish causal links between gambling and harms.”

“Although we need further research to understand the extent of the causal relationship between harmful gambling and impacts, this research allows us to examine the financial costs to government and the societal value of the health impacts associated with harmful gambling.”

Uncertainties are further recognised in the “appropriate assumptions to estimate the number of deaths by suicide associated with harmful gambling,” in which the report followed the advice of its expert panel to ‘present a range of values’.

Once more the “the range reflects the limits of the evidence available as well as the sensitivity of the costs to the number of deaths by suicide”. Thus the expert panel noted that presenting a range of values on suicide was determined as an improvement on methodology.

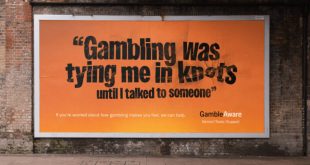

As the review progresses into its final stages, Rishi Sunak – the third Prime Minister to oversee the process – has heeded the advice of senior NHS clinicians to place the focus of the debate on the links between gambling harms and suicide.

The findings from PHE’s research, which places suicide as the either the first or second biggest cost of gambling harm, appears to show that this narrative is being upheld by government departments.

The close of 2022 saw UK media report that the PM would demand ‘cabinet unity’ to order the toughest measures to fix the gambling sector. The PM was reported the have ‘listened to the experts’ who cited gambling suicide prevention as the review’s mist urgent matter.

The final sting in the curtain closer of the Gambling Review, pledged by DCMS to be published in February, the White Paper of recommendations will reveal exactly which experts Sunak has been listening to.